Saudi Arabia has an estimated population of 32 million, the 40th largest in the world and 6th largest in the Arab world. It is barely more than a third of the size of Egypt’s population. Territorially, however, Saudi Arabia is massive. It is the 12th largest country in the world, and the largest country in the Arab world outside of Algeria. Its territory is roughly the size of Turkey, France, Germany and Japan put together.

Of course, much of this territory is desert. Saudi Arabia’s arable land per capita, according to the World Bank, is just 0.1 hectares per person. This is less even than in densely populated states like India, though it is still a lot higher than in Egypt, Yemen, and a few other Arab countries.

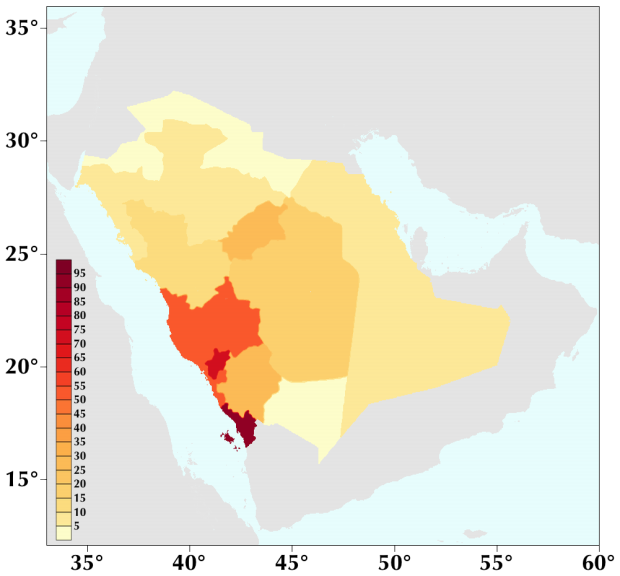

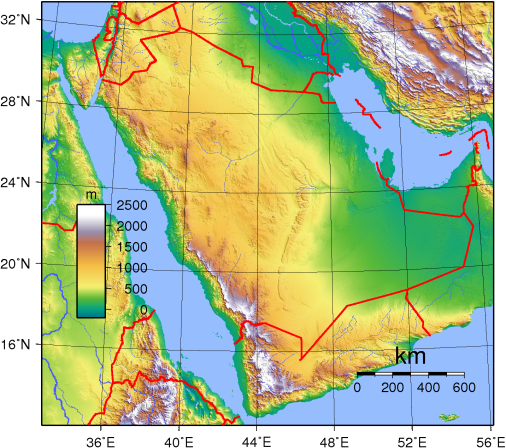

Most Saudis live in the western part of the country, within 150 km of the Red Sea. The densest concentration of Saudi Arabians live near the country’s mountainous border with Yemen.

On the Yemeni side of the border the population density is also high. Nearly all of Yemen’s population of 27 million lives within 400 km of this border. Many Yemenis live within just 200 km of the border, in the capital and largest city Sana’a or in the mountains north of Sana’a.

This populous border region is inhabited by a non-Sunni majority on both sides of the border, in stark contrast to Saudi Arabia as a whole. It has created challenges for the Saudi rulers. In recent years the Saudi military has been engaging directly in the ongoing Yemeni civil war, for example.

(Another product of Yemeni-Saudi relations was Osama bin Laden, one of the many sons of the billionaire Mohammad bin Awad bin Laden, a poor Yememite who moved to Arabia’s main port city of Jeddah before the First World War, who went on to become one the richest non-royals in Saudi Arabia).

The Saudi-Yemeni relationship is in some ways a microcosm of Saudi Arabian geopolitics in general. Saudi Arabia’s borderlands (the lands on either side of Saudi Arabia’s borders) are much more populous than Saudi Arabia’s heartland (the region in and around the Saudi capital city Riyadh). While the Saudi heartland adheres mainly to ultraconservative Wahabbi Islam (or, more broadly, to Sunni Islam), Saudi borderlands are often non-Sunni or adhere to more cosmopolitan (by Saudi standards) non-Wahabbist Sunni traditions.

This includes not just the wealthy, relatively cosmopolitan foreign cities of the Persian Gulf, like Dubai, Doha, or Abu Dhabi, but also cities within Saudi Arabia near the Red Sea, like Mecca and Medina (because of the Hajj, which has historically had a worldly influence) and the Meccan port city of Jeddah, which is by far the most populous Saudi city apart from Riyadh.

Within 200 km of Saudi Arabia’s land borders, over 35 million people live (not counting Saudi Arabia’s own population), more than the 32 million people that live in Saudi Arabia. Within 500 km of Saudi Arabia’s land or sea borders more than 230 million people live (not counting Saudis). By comparison, there are just 15 million or so people who live in or within 500 km of Riyadh.

In contrast, in Egypt most of the Egyptian population lives in or within 200 km of Cairo, and very few people in Egypt live within 200 km of Egypt’s land borders with other countries. In Turkey most people live in or within 400 km of the capital Ankara. In Iraq nearly all people live in or within 430 km of Baghdad. And in Pakistan most people live within 500 km of Islamabad.

Iran, on the other hand, does have a somewhat similar geopolitical configuration as Saudi Arabia, if not necessarily to the same extreme. The Iranian heartland (in, around, and between the cities of Tehran and Esfahan) is far away from most the country’s populous borderlands, and its borderlands are in many cases not inhabited by Persians but rather by minority groups like Kurds, Arabs, Azeri Turks, Balochis, and others. The fact that both Saudi Arabia and Iran are potentially fragile in this way has helped, perhaps, to drive their rivalry with one another, as both act aggressively to preempt any perceived threats to their internal cohesion.

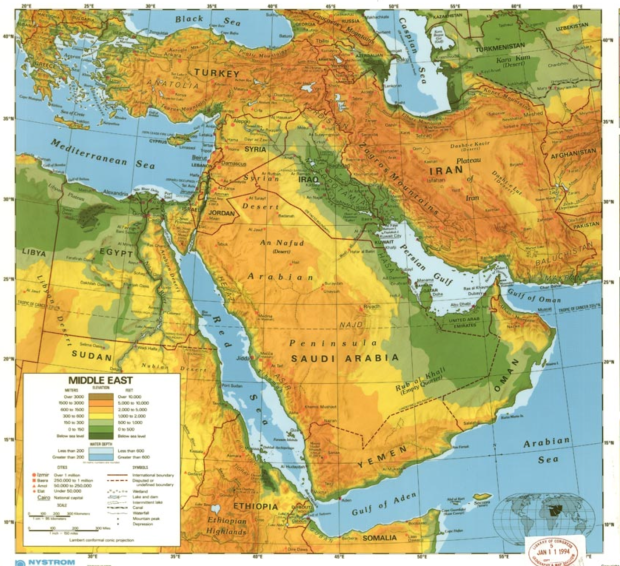

One of the only significant exceptions to Saudi Arabia’s borderland permeability is in its southeast, where the Empty Quarter of the Arabian desert effectively hives off areas within Oman, the UAE, and Yemen from Saudi population centres. You can see the influence of the Empty Quarter (Ar Rub’ al Khali) in the map of roads in Saudi Arabia below: it has almost none. According to Wikipedia, the Empty Quarter is larger in size than entire countries like France, Afghanistan, or Ukraine. It is about five times larger than England.

Looking out from Riyadh, the Saudi leadership sees potential border-region threats in almost every direction. It worries not only about neighbouring countries, but also how they may interact with its own Saudi citizens (and with its foreign-born labourers, who number around a fifth of the people in Saudi Arabia). In the past the Saudis have waged an aggressive foreign policy meant to stave off such threats, for example allying with the US during the Cold War in order to combat the Shiite Iranians (post-1979), the Pan-Arab Nasserites in Egypt (pre-1980), and Ba’athist Iraq (in 1990).

Today Saudi Arabia continues to project influence, in various ways, into countries like Egypt (where it supported ultra-religious Salafist political parties and the Egyptian military against both the Muslim Brotherhood and Egyptian liberals), Bahrain (which Saudi Arabia invaded, in effect, during the Arab Spring in 2011, in order to prop up the Sunni monarchy against the majority Shiite population), Iraq and Syria (where it has supported religious Sunni groups), Lebanon, and Yemen.

Even along its maritime borders the Saudis are potentially insecure, a result of the narrowness of the Red Sea (250 km, on average) and Persian Gulf (also 250 km wide), as well as the fact that both seas can be potentially closed off because of the chokepoints of Hormuz, Suez, and the Bab-el Mandeb. Indeed, absent support for Saudi Arabia from an outside power like the United States, the most probable leading nation in the energy-rich Persian Gulf is not Saudi Arabia, but rather is Iraq, which occupies a large majority of the arable lowlands in the Persian Gulf basin, or Iran, which occupies most of the arable highlands overlooking the Persian Gulf. Saudi Arabia’s Gulf region, in contrast, is mainly desert.

In addition, because Iran and Iraq are both majority-Shiite, as is Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province and neighbouring Bahrain, the Sunnis and Wahabbists in Saudi Arabia are at a potential disadvantage in the Gulf region from a religious perspective. Indeed, Saudi Arabia is badly outnumbered in the Gulf even just by the Kuwaitis, Qataris, and Emiratis, who together have 15 million inhabitants (led by the Emiratis, with 9.5 million people) and an estimated GDP of 775 billion dollars (compared to around 750 billion dollars for Saudi Arabia). This situation is further complicated by the huge foreign-born labour forces of these rich Gulf monarchies, which tend not to be treated very well yet outnumber the citizen labour forces within most of these countries.

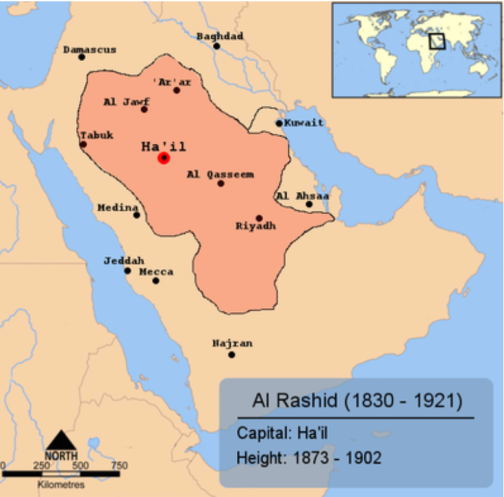

Historically the Persian Gulf was not as important as it is in the modern oil and gas era. The Saudis main rivalries in the late 19th and early 20th century were instead in western Saudi Arabia, with the Hashemites, and in north-central Saudi Arabia, with the Rashidis. The Hashemites, who had been allied with the British and today rule Jordan, were in control of the Hejaz (see map below) until defeated and exiled to (rule) Iraq, Syria, and Jordan by the Saudis in 1924-1925; the Rashidis, who had at times been allied with the Turkish Ottomans, were in control of most of the Arabian interior until defeated by the Saudis in 1921, three years after the end of the First World War. Just thirty-one years before, in 1890, the Rashidis had conquered Riyadh and forced the Saudis into political exile in Bahrain, Qatar, and Kuwait.

Today most of Saudi Arabia’s population lives in the Hejaz, in lands that have been under Saudi rule for less than a century. The legacy of the rivalry between the Saudis and Rashidis, meanwhile, can still be seen in the M. Izady relgious map (posted higher above in this article), where the area in, around, and north of the city of Ha’il, the former Rashidi capital, is one of the only parts of the Saudi interior categorized as Sunni rather than Wahhabi. The defeat of the Rashidi dynasty has meant that Ha’il is now just the 12th most populous city in Saudi Arabia, in contrast to Riyadh which has become the largest in the country.

Mecca and Medina

Mecca is just the third most populous Saudi city, however because of its religious significance it is more important than any other. It is located close to other large Saudi cities: 65 km east of Jeddah (the second largest Saudi city, with more than twice the population of Mecca), 50 km west of Taif (the sixth largest Saudi city) and 335 km south of Medina (the fourth largest Saudi city). Together Mecca, Jeddah, and Taif, all of which are located in Makkah Region, have a population larger than the Saudi capital Riyadh or the Riyadh Region.

Mecca is located almost exactly on a straight line with Riyadh in central Saudi Arabia (I’ve added lines on the map above to try to display this), with Hofuf and Dammam in eastern Saudi Arabia (the fifth and seventh largest Saudi cities, respectively), and with Manama (Bahrain’s capital) immediately to Saudi Arabia’s east. This line is perpindicular to the line that runs north-south along the western coast and coastal mountains of Arabia.

Within these lines, which converge around Mecca, Jeddah, and Ta’if, lives a significant majority of Saudi Arabia’s population, as well as most Yemenis and Bahrainis. Cities like Medina, meanwhile, are outside but still quite close to these lines, as is Doha the wealthy capital of Qatar. The north-south line also runs roughly parallel to the Nile river valley, where nearly all Egyptians and most Sudanese live.

Historically Mecca and Jeddah were strategically located, at the centre of the regional trade and transport routes linking Asia, Europe, and East Africa. They are situated almost exactly 1200 km from the Indian Ocean, Mediterranean, and Persian Gulf. Because Mecca and Jeddah are located just to the north of the higher elevations of Arabia’s Red Sea coastal mountains (see maps below), and northwest of the impassable Empty Quarter of Arabia, caravan routes between the Persian Gulf and Red Sea could not easily bypass them to the south.

At the same time, Mecca still has a useful foothold in a small northern sliver of these higher-elevation coastal mountains, around Ta’if. Ta’if, where Meccan elites historically would reside during the summer to escape the heat, is at 1879 metres above sea level, compared to just 12 metres for Jeddah, 277 for Mecca, and 332 for Medina.

The relative proximity of Mecca, Jeddah, and especially Medina to Egypt was also significant in the past. Before steamships, it was difficult to travel northward in the Red Sea because of the trade winds blowing south and the rockiness and narrowness of the Gulf of Suez. As a result, ships would often travel instead to the Egyptian port city of Al-Qusayr (population 50,000 today) where a bend in the Nile brings the river relatively close to the Red Sea, then cross 155 km of desert overland to Quena (population 250,000) on the Nile and sail the river the rest of the way to the Mediterranean.

Unlike the Red Sea, the Egyptian portion of the Nile could be crossed easily in either direction; it has no significant rapids or water-barriers to the north of the Cataracts of the Nile (which separate Egypt from Sudan), it has no significant river bends (unlike the very big bend the Nile makes in Sudan north of the capital Khartoum), and even sailing south against the current of the river could be acheived with relative ease because of the south-blowing trade winds. The Egyptian port of Al-Qusayr on the Red Sea is not too far north of Medina, and is likely one of the reasons that Medina became so significant.

In addition, Medina is located near where the Wadi Al-Rummah, the longest valley in the entire Arabian peninsula, arises. It runs from Medina all the way northeast to the Persian Gulf by Kuwait.

Jeddah and Mecca, meanwhile, are across from Port Sudan, which is by far the most populous coastal city on the Red Sea in either Sudan or Egypt (not counting Suez). From Port Sudan a valley leads through the East African coastal mountains to the Sudanese capital of Khartoum (population 5-6 million), where the Blue Nile and White Nile meet to become the Nile. Today Khartoum is perhaps the fourth or fifth most populous city in the Arab world, but gets little media attention.

The routes between Arabia and the Nile were used, for example, during the late 18th century, when the British sent their army from India to Egypt to counter the invasion of Egypt and Palestine by Napoleon, when Napoleon was still a general and not yet France’s ruler. The route was used also by the sons of Egypt’s Ottoman Viceroy Muhammad Ali to overthrow the First Saudi State (1744-1818) and later challenge the Second Saudi State (1824-1891). However as a result of modern shipping and the Suez Canal, the route today is no longer as important.

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia’s geography has heavily informed its history, up to and including the present day. As a result of its desert climate, for example, the Saudi economy is still not very large. Its GDP is estimated to be smaller than Turkey’s, a third as large as Italy’s, and less than twice as large as those of Iran or the United Arab Emirates. Politically, meanwhile, the strain between the historical Saudi and Wahabbi heartland around Riyadh and its borderlands around the Red Sea and Persian Gulf is perhaps the main factor driving the Saudi state’s aggresivity and extremism, both at home and abroad. This aggressivity and extremism, in turn, could create political pushback against the Saudi leadership from Saudi citizens, neighbouring Middle Eastern countries, or external powers like the United States.

————–

Some notes, taken from Wikipedia:

The Rashidis

“As with many Arab ruling dynasties, the lack of a generally accepted rule of succession was a recurrent problem with the Rasheedi rule. The internal dispute normally centered on whether succession to the position of amir should be horizontal (i.e. to a brother) or vertical (to a son). These internal divisions within the family led to bloody infighting. In the last years of the nineteenth century six Rasheedi leaders died violently. Nevertheless, The Al Rasheed Family still ruled and fought together [against the Saudis] in the Saudi–Rashidi Wars.”

As an aside, Faisal bin Musa’id, a half-Rashidi half-Saudi prince, assisinated Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal in 1975. According to Wikipedia, “Faisal’s father was Prince Musa’id, the step-brother of King Faisal, and his mother was Watfa, a daughter of Muhammad bin Talal, the 12th (and last) Rashidi Emir. His parents divorced. He and his brothers and sisters were much closer to their maternal Rashidi relatives than their paternal Al Saud relatives. In 1966, his older brother Khaled, a Wahhabist, was killed during an assault on a new television station in Riyadh. Wahhabi clerics opposed the establishment of a national television service, as they believed it immoral to produce images of humans. The details of his death are disputed. Some reports allege that he actually died resisting arrest outside his own home. Faisal came to the United States in 1966 and attended San Francisco State College for two semesters studying English. Allis Bens, director of the American Language Institute at San Francisco State, said, “He was friendly and polite and very well brought up it seemed to me. I am really very surprised about this.” While Faisal was at San Francisco State his brother Khaled was killed. In 1969, while in Boulder he was arrested for conspiring to sell LSD. He pleaded guilty and was place on probation for one year. After leaving the United States, he went to Beirut. For unknown reasons, he also went to East Germany. When he came back to Saudi Arabia, Saudi authorities seized his passport because of his troubles abroad. He began teaching at Riyadh University and kept in touch with his girlfriend, Christine Surma, who was 26 at the time of the assassination.On 25 March 1975, he went to the Royal Palace in Riyadh, where King Faisal was holding a majlis. He joined a Kuwaiti delegation and lined up to meet the king. The king recognized his nephew and bent his head forward, so that the younger Faisal could kiss the king’s head in a sign of respect. The prince took out a revolver from his robe and shot the King twice in the head. His third shot missed and he threw the gun away. King Faisal fell to the floor. Bodyguards with swords and submachine guns arrested the prince. The king was quickly rushed to a hospital but doctors failed to save him. Before dying, King Faisal ordered that the assassin not be executed.. Saudi television crews captured the entire assassination on camera. A sharia court found Faisal guilty of the king’s murder on 18 June, and his public execution occurred hours later. His brother Bandar was imprisoned for one year and later released. Following the execution, his head was displayed to the crowd for 15 minutes on a wooden spike, before being taken away with his body in an ambulance. Beirut newspapers offered three different explanations for the attack. An-Nahar reported that the attack may have been possible vengeance for the dethroning of King Saud, because Faisal was scheduled to marry Saud’s daughter — Princess Sita — in the same week.”

The First Saudi State

“After many military campaigns, Saud [the founder of First Saudi State] died in 1765, leaving the leadership to his son, Abdul-Aziz bin Muhammad [who married the daughter of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the founder of Wahabbism]. Saud’s forces went so far as to gain command of the Shi’a holy city of Karbala [in Mesopotamia] in 1801. Here they destroyed grave markers of saints and monuments. [Later they] sent out forces to bring the region of Hejaz under his rule… This was seen as a major challenge to the authority of the Ottoman Empire, which had exercised its rule over the holy cities since 1517. The task of weakening the grip of the House of Saud was given to the powerful viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, by the Ottomans This initiated the Ottoman–Saudi War, in which Muhammad Ali sent his troops to the Hejaz region by sea. His son, Ibrahim Pasha, then led Ottoman forces into the heart of Nejd [the interior of Arabia]… Finally, Ibrahim reached the Saudi capital at Diriyah [on the outskirts of Riyadh] and placed it under siege for several months until it surrendered in the winter of 1818. Ibrahim then shipped off many members of the clans of Al Saud and Muhammed Ibn Abd Al Wahhab to Egypt and the Ottoman capital, Constantinople. Before he left he ordered a systematic destruction of Diriyah, whose ruins have remained untouched ever since. Abdullah bin Saud was later executed in the Ottoman capital Constantinople with his severed head later thrown into the waters of the Bosphorus, marking the end of what was known as the First Saudi State.”

The Second Saudi State

“The first Saudi to attempt to regain power after the fall of the Emirate of Diriyah in 1818 was Mishari ibn Saud, a brother of the last ruler in Diriyah, Abdullah bin Saud. He was soon captured by the Egyptians and killed, however. In 1824, Turki bin Abdullah bin Muhammad, a grandson of the first Saudi imam Muhammad bin Saud, was able to expel Egyptian forces and their local allies from Riyadh and its environs. He is generally regarded as the founder of the second Saudi dynasty as well as being the ancestor of the kings of modern-day Saudi Arabia. He made his capital in Riyadh and was able to enlist the services of many relatives who has escaped captivity in Egypt, including his son Faisal ibn Turki Al Saud. Turki was then assassinated in 1834 by Mishari ibn Abdul-Rahman, a distant cousin. Mishari was soon besieged in Riyadh and later executed by Faisal, who went on to become the most prominent ruler of the Saudis’ second reign. Faisal, however, faced a re-invasion of Najd by the Egyptians four years later. Faisal was defeated and taken to Egypt as a prisoner for the second time in 1838. The Egyptians installed Khalid ibn Saud, last surviving brother of Muhammad bin Saud, who had spent many years in the Egyptian court, as ruler in Riyadh, and supported him with Egyptian troops. In 1840, however, external conflicts forced the Egyptians to withdraw all their presence in the Arabian Peninsula, leaving Khalid with little support. Seen by most locals as nothing more than an Egyptian governor, Khalid was toppled soon afterwards by Abdullah ibn Thuniyyan, of the collateral Al Thuniyyan branch. Faisal, however, had been released from prison that year and, aided by the Al Rashid rulers of Ha’il, was able to retake Riyadh and resume his rule… Upon Faisal’s death in 1865, Abdullah assumed rule in Riyadh but was soon challenged by his brother, Saud. The two brothers fought a long civil war, in which they traded rule in Riyadh several times. Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Rashid of Ha’il took the opportunity to intervene in the conflict and increase his own power. Gradually, Ibn Rashid extended his authority over most of Najd, including the Saudi capital, Riyadh. Ibn Rashid finally expelled the last Saudi leader, Abdul-Rahman bin Faisal, from Najd after the Battle of Mulayda in 1891, ending the Second Saudi State.”

very interesting post

thank you Mukul! much appreciated

welcome

Relating to your final paragraphs, this article here is very, very good:

View at Medium.com

Really interesting article, thanks. I’m going to start following his website too

This is a very interesting geographic analysis. The Arabian Peninsula is much more complex in terms of religion, ethnicity, and geography than is given credit for. There is plenty of desert and it’s a prominent feature. However, there is more to consider, especially with Yemen.

I would also like to point to something else. You do show that resources often play a factor in geopolitics. Oil is an example of this. On that note, there is another resource that is going to play a role: Water. Water resources already constitutes a large factor in the geopolitics of the Middle East region. Oil is a big part. So is water. Water doesn’t get as much attention though.

Absolutely, you’re right about that